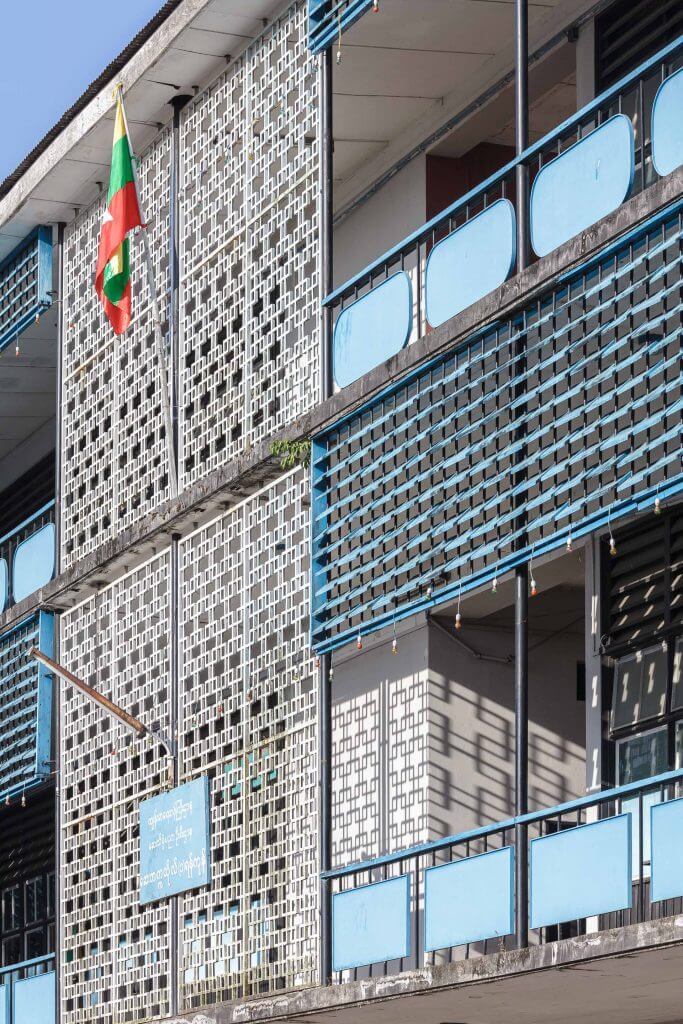

Formerly: Rangoon College of Engineering

Address: Pyay Road

Year built: 1954-1956

Architect: Raglan Squire

The architectural profession in post-independence Myanmar began with the introduction of a degree programme at Rangoon University in 1954. It took another four years for the first five students to graduate. U Tun Than, who designed the Children’s Hospital in Dagon township, was in that first small cohort. Back then, all the students knew Raglan Squire.

Squire was born in London in 1912 and read architecture at Cambridge in the interwar years. He founded his first practice in 1937, but would soon serve with the Royal Engineers during the war. He was an influential member of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) Reconstruction Committee during the rebuilding of London after the war. His conversions of townhouses into apartments on Eaton Square, in Belgravia, are especially notable.

Squire was chosen to build the new Engineering College of Rangoon University. This was evidence of the government’s desires to attract a forward-looking, international architect to post-independence Yangon. Squire first came to Rangoon in November 1953. For the Brit, the “contrast to fog-bound, cold London, was too much”. He was taken on a night time drive through the streets of Yangon and, in his autobiography, writes that he fell in love with Burma and the Burmese that night. His plans for the complex delighted the government, who pushed him to start building as soon as possible—Prime Minister U Nu came to lay the foundation stone. Squire brought a large team of experienced architects and engineers from the UK. The total payroll exceeded 100 people, although it was bloated by extensive domestic staff employed by the expats.

Just like Squire’s Technical High School, this was a comparatively expensive building for impoverished post-independence Burma. Funds were made available via the Colombo Plan and were therefore indirectly provided by the Americans. For those countries in the region that had strong domestic communist movements, accepting aid outright from the United States was politically contentious. It was also the aspiration of many newly independent nations in Southeast Asia to be perceived as non-aligned. Therefore, accepting funds and technical assistance from a multilateral mechanism like the Colombo Plan was an expedient loophole.

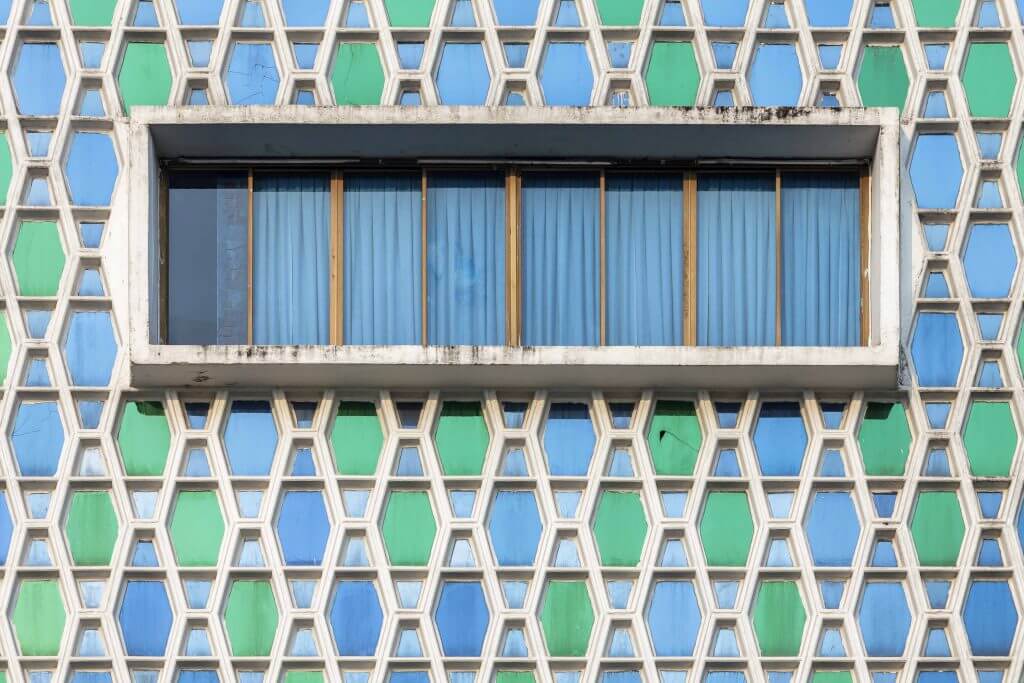

As you approach the complex, the main library building sits perpendicular to the street and is visible from far down Pyay Road. Note the canopy covering the entrance area. A large rectangular window on the street-facing side appears like the only opening of the tall building’s façade. Raglan Squire said of the Library building, the tallest in Yangon at the time:

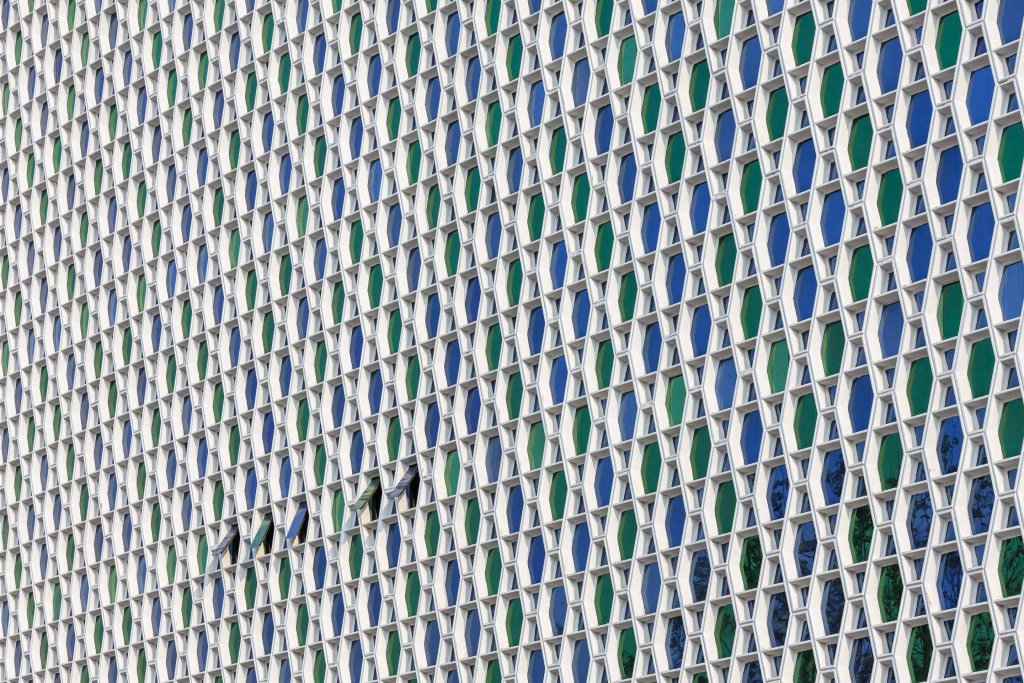

“The Library building would be multi-storey and, therefore, presented different problems. I finally decided that I would clad the whole of this building with precast, coffin shaped, panels; into these panels I would fit different coloured glass strips assembled in the form of louvres. The result would be a building that would be gently ventilated, through the louvres, along its total length and which would receive, through the different coloured glass, a kind of dappled daylight effect like the lightning in a tropical jungle.”

The rest of the complex consists of lower building wings containing more lecture theatres and classrooms. In a time before air conditioning, the overarching design inspiration was the extreme climate (a recurring feature in this book, as you may have noticed).

Squire personally commissioned Burmese artists to design various murals and bas-reliefs in the courtyard; these have been very well preserved. Just like the ones installed at the Technical High School, they portray idyllic and optimistic displays of traditional life in a (newly) independent Burma. It is worth exploring the entire compound, which at 60 years of age exudes the same forward-looking modernity of its younger days.

Raglan Squire regarded this commission as the high point of his career (which continued until his retirement in 1981). What earned him the most attention internationally were not the concrete buildings, but a structure that has since disappeared. Indeed, Squire also designed a wooden assembly hall, which locals quickly dubbed “Laik Khone” (“back of the tortoise”) due to its peculiar shape. It was a remarkable piece of timber engineering, its stability testimony to the quality and resilience of Burmese teak. In some places of the concave assembly hall’s structure, eight layers of wood were stacked on top of each other, made possible by advances in timber design techniques. Better adhesives, timber connectors and novel prefabrication methods contributed to the achievement too.

Unfortunately, the maintenance of the hall proved cumbersome and expensive. Amid the economic hardships of the post-1962 socialist period, the structure deteriorated and was eventually torn down around 1980. Squire initially planned for the hall to be built of reinforced concrete. Had that been done, would it still be standing today?

The opening ceremony in 1956 was a notable event in post-war Rangoon. Raglan Squire describes it the following way:

“The Library building I lit from the inside so that all the little coloured glass, coffin-shaped windows sparkled like a Christmas tree. The Assembly Hall was brightly lit inside and we arranged for a gentle flow of lighting outside; the roof looked like the humped back of a giant turtle. The buffet tables each had their own oil lamps, the pweis glittered as on the street on my first night [in Rangoon]—and the whole complex was alive with happy, laughing people. The crowds were so great that we held up the traffic for hours on the main Prome [Pyay] Road out of Rangoon. It was a great day and great evening. I went to bed happy—yet with a little tinge of sadness. Could anything quite so magnificent ever happen again for me, personally, in the rest of my life? I have had many great days since but, truly, never one quite like that.”

In 1961—only five years after it had moved into the brand new building complex —the architecture department was again relocated. This time, the move took it from the indirectly US-funded and British-designed facilities into the newly built Institute of Technology, which—tellingly—was donated by the Soviet Union.

Squire had left Burma a long time before then. Subsequent assignments took him around the world, including the Middle East where he built the Tehran and Bahrain Hilton hotels, an airport in Baghdad and a town-planning scheme for Mosul. Squire had a long retirement and passed away in 2004. His son Michael is the principal of the London-based architectural firm Squire and Partners, whose most notable projects include the Chelsea Barracks and the Shell Centre redevelopment, both in London. His firm should not be confused with the Singaporean heir to Squire’s name, RSP (short for Raglan Squire & Partners, which Squire founded shortly after leaving Burma). The firm continues to be involved in Yangon today, but makes no reference to its founding father on their website. RSP built the Sule Shangri-La in the 1990s and participates in the proliferation of rather nondescript mixed-use developments around Yangon, such as the planned Gems Garden project west of Inya Lake.

While RSP may have strayed, it seems, from the grand designs of its founder, we hope this guide can at least help put to rest a worry that Squire recounts in his autobiography, as he departed from Burma in the 1960s: “I wanted to do something great. I knew I had done a good job in Rangoon but, with Burma slipping into self-imposed obscurity, who on earth would ever see my buildings there?”

We need more architectural writings for younger students and also for master degree students.

Thank you so much, indeed!