Naypyidaw is Myanmar’s new, shining and purpose-built capital. Empty highways connect its huge and often baffling buildings. Bearing signs of the regime’s uneasy relationship with Yangon, the city shows a conscious desire for strategic isolation and a new national narrative. But can it grow into the role?

Although there had been rumours, the news still caught many people unawares.

Practically overnight, on Sunday, 6 November 2005, the military authority moved the country’s entire government from Yangon to a new, purpose-built city 320 kilometres to the north, about halfway up the road to Mandalay. Its name was Naypyidaw, or “abode of kings”. An almost virgin site was chosen for this bold experiment, west of a small town called Pyinmana. The terrain was so remote that few people grasped its scale. Nearby residents reported seeing Chinese contractors in Pyinmana’s tea shops as early as 1999. Some observers expected a major new Tatmadaw (army) headquarters here. But early on that Sunday morning, a large convoy of trucks loaded with the contents of entire ministries started their engines and left Yangon, heading north.

Naypyidaw transformed the country’s political geography. Since the British occupied Lower Burma in 1852, and Upper Burma in 1885, Myanmar’s centre of gravity had moved to the south, away from the historic Burmese heartlands of its former capitals, Amarapura, Ava, Mandalay and Pagan. Under British rule the hitherto quiet and swampy Yangon became the country’s economic and political heart. As we discuss in the section on post-1988 Yangon, when the military enacted urban planning policies in response to the pro-democracy movement, the changes they eventually imposed on Yangon failed to give the generals much peace of mind. Instead the junta continued to distance itself from the city; the generals deemed it an unnatural capital. But with Naypyidaw, they didn’t just create a physical distance from Yangon, or indeed any other city—they also insulated themselves from their people.

Many saw this as a defensive move. Naypyidaw is far from the coast, where it could fall victim to a foreign invasion. Naypyidaw is on a hill. Naypyidaw is closer to the country’s conflict areas where episodic violence has flared between ethnic minority armed groups and the Tatmadaw, although a draft national ceasefire was signed in April 2015. Whatever the motivations, the cost of building a city from scratch in one of Asia’s poorest countries is—ultimately—indefensible: the government has spent an estimated 4–5 billion US dollars on Naypyidaw already. And judging from construction activity and the city’s scale, the total invoice will continue to grow.

Naypyidaw’s urban layout bears a strong resemblance to American suburbs and strip malls. Economic, residential and even hotel zones are strictly segregated. The hotel district lies adjacent to the (largely undeveloped) diplomatic housing compound. Predictably, given the dearth of city life, most diplomatic missions have chosen to remain in Yangon so far. The ministry area is 10 kilometres to the north. As a city built exclusively for motor vehicles, it doesn’t provide for pedestrians outside gated shopping and hotel complexes, which often offer golf carts for transportation given their vast dimensions. This is a city without an easily discernible centre—perhaps no accident. The symbols of power, above all the gigantic parliament building, are not easily accessible. No public space surrounds them. Whether these are conscious security measures or results of poor urban planning is a matter of debate. In the eyes of journalist Siddharth Varadarajan, Naypyidaw “will always lack the urban cadences and unpredictable rhythms that characterise city life in Rangoon or Mandalay. And this is precisely what makes the new capital so attractive to the generals.”

Large sporting venues had been built for the Southeast Asian Games that were held here in 2014. In a city full of curiosities, the Wunna Theikdi and Zeyar Thiri sporting complexes may be the most revealing: they are perfectly and eerily identical, despite being 35 kilometres apart. They both contain an outdoor stadium, three indoor stadiums, a swimming complex and indoor halls. (The contractor in both cases was Max Myanmar, one of the country’s largest and best-connected conglomerates.)

These are not the only surreal copycats. The new capital’s City Hall is a replica of Yangon’s. The Uppatasanti Pagoda is almost an exact copy of the Shwedagon Pagoda. It is one foot shorter and its base is hollow, but from the outside the illusion is almost perfect. This complicates our earlier point about Naypyidaw symbolising a clean break from Yangon. In these cases, the intention may be to overwrite the originals or take away from their unique symbolic and political power.

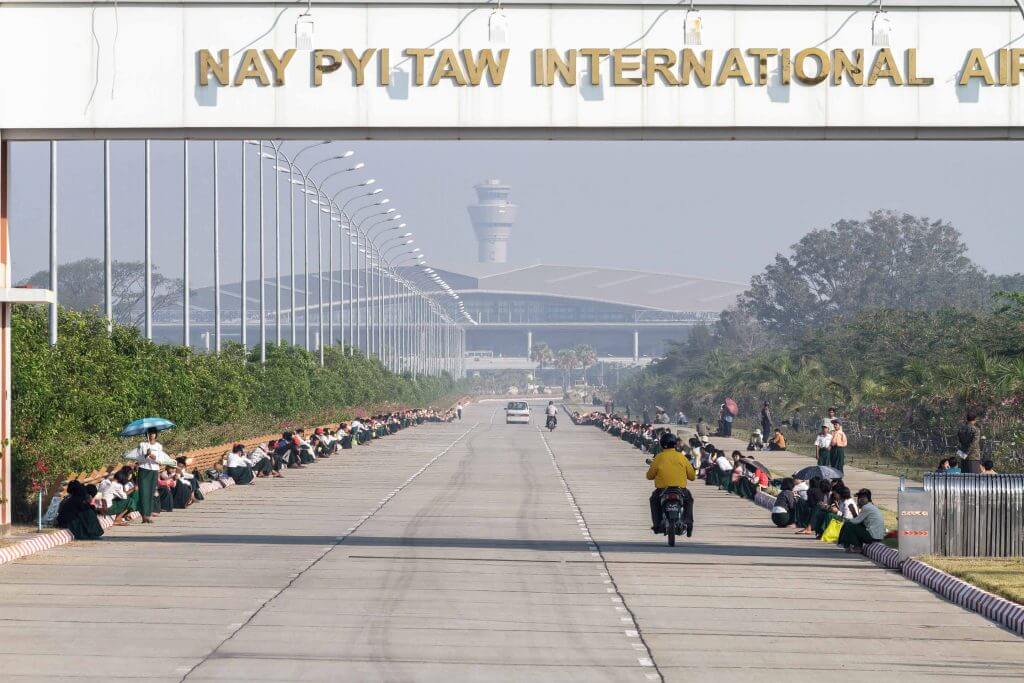

The gigantic Myanmar International Convention Centre was built by Chinese contractors and with Chinese money. If you aren’t visiting the city for a major event or conference there, you may feel very lonely in Naypyidaw’s vast airport. As of early 2015, the only international connections include Kunming (in China’s Yunnan province), Kuala Lumpur and nearby Bangkok. It was designed by Singaporean CPG Corporation and built by Myanmar conglomerate Asia World.

You will waste no time in traffic jams here: Naypyidaw boasts what is probably the most under-used ten-lane highway on earth. You may see water buffalos having a snooze right in the middle of it, which tells you how often they’ve felt confronted by passing cars. The highway is especially wide in front of the Hluttaw (parliament). Maybe history will prove these ambitious highway planners right. Until then, the experience remains surreal, enhanced by the beautifully manicured flowerbeds at a number of equally massive roundabouts.

Leave Naypyidaw for one of the surrounding towns, the closest being Pyinmana, just behind a crest from Uppatasanti Pagoda, and you return to ordinary Myanmar with bustling traffic, vibrant street life and a scale shrunk back to human proportions. A tree-lined road alongside the railway tracks used to be the only connection to Yangon before the construction of the Yangon-Mandalay Expressway. Follow this road to the south and it intersects with the arterial road which links Naypyidaw International Airport with the new capital.

In being a new and—to start with at least—artificial capital, Naypyidaw has various precedents around the world. Besides historical examples in the United States, Australia, Russia and Canada, there were prominent capital relocations more recently in Brazil (from Rio de Janeiro to Brasilia), Kazakhstan (Almaty to Astana), Belize (Belize City to Belmopan) and Nigeria (Lagos to Abuja). It takes decades to judge their success. Of those examples, Naypyidaw is not the only purpose-built capital created for military and strategic reasons.

The opening-up of the country is also changing Naypyidaw and the way we may come to think about it. The grotesquely huge parliament building (Pyidaungsu Hluttaw) has played host to, in some eyes, surprisingly vibrant debates on new laws and regulations. The opposition National League for Democracy (NLD) has had MPs here since a by-election in 2012, including opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi. And while we cannot guess for certain the outcome of the 2015 elections, the oft-quoted democratisation process will doubtless shape the city’s dynamic. It presents a fascinating case of a place planned by authoritarian rulers for the purpose of spatial isolation, confronted with the imperative now to grow into the deserving capital of an aspiring democracy—although the speed, depth and sustainability of that purported transition is contentious.

Much media coverage of Naypyidaw will no doubt focus on the oddities resulting from its undemocratic and secretive genesis: a zoo boasting an air-conditioned penguin house, deserted highways and bulky government buildings—these will be Naypyidaw’s trademarks for years to come. For now, its abiding legacy is anyone’s guess.