Formerly: National Bank of India

Address: 26–42 Pansodan Street

Year built: Circa 1930

Architect: Thomas Oliphant Foster & Basil Ward

The National Bank of India (NBI) was one of the main exchange banks of the British Empire. Its Rangoon branch was set up in 1885 and a stately headquarters was erected on Pansodan Street by 1896.

In the 1920s, business was booming in this part of the world. The company decided to rebuild its branch from scratch—this time bigger, more opulent—and decidedly more modern.

The new building was finished around 1930, designed by Thomas Oliphant Foster and Basil Ward. We cover Foster’s legacy in the Myanma Port Authority section. But a few words about Ward are warranted here because his name is practically forgotten in connection with Yangon. Foster was the more experienced member of the short-lived duo but Ward (1902–1976) contributed the flair of a young architect fresh out of school. He leant towards the modern architectural language of continental Europe. A native New Zealander, he studied in Wellington and moved to London upon graduation in 1924. He failed to enrol at the prestigious Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) and, after a while, moved to Yangon with his wife. Here Foster and Ward worked on a variety of buildings that are usually exclusively credited to Foster. Apart from the NBI building, these projects include the Myanma Port Authority as well as several buildings for Yangon University. Ward returned to London in 1930, setting up a partnership with his friend from home, noted modernist architect Amyas Connell. They teamed up with London-born Colin Lucas in the mid-1930s to form a short-lived but highly influential partnership. They were among the foremost proponents of pre-war International Style architecture in Britain and designed residential projects in and around London, several of which still stand today. Along with Raglan Squire (see the Technical High School and University of Medicine-1), Basil Ward is one of a small group of architects who used their stints in Rangoon to further their international careers.

The National Bank of India building is often known as the Grindlays Bank. What follows is a tale of mergers and acquisitions in high finance, as played out on Pansodan Street in downtown Yangon: Grindlays only entered Burma after it acquired Thomas Cook & Sons in 1942. (Back then, the travel agent also had banking operations—remember travellers’ cheques?) Besides Thomas Cook’s Rangoon branch on Merchant Road, Grindlays also acquired buildings in major cities in China, India as well as Hong Kong, Ceylon and Singapore. As the Japanese army had occupied Rangoon, Grindlays had to wait almost four years before it could formally requisition its branch there a few months after the war. Grindlays’ owners, National Provincial (later merged into today’s NatWest), sold Grindlays to NBI in 1948. Ten years later NBI and Grindlays merged into the new National Overseas & Grindlays Bank. This building was their office. The name change reflected many companies’ desire to rid themselves of references to the former Empire. This was, to put it politely, out of fashion in the post-colonial age. After all NBI was no Indian bank and “National and Grindlays”, as it became known, sounded more forward-looking. In Yangon popular parlance however, the bank became known simply as “Grindlays Bank”. (This revelation concluded the rather arduous task of locating this building for this book’s research.)

In 1961 National and Grindlays Bank bought Lloyd’s Bank, which had a branch just across Pansodan Street, today’s Myanmar Economic Bank Branch 1. Eventually, as with all banks in socialist Burma, National and Grindlays underwent its last and final merger, this time a forced one: in 1963 it was nationalised and became the “People’s Bank No. 11”.

From 1970 to 1996, this building housed the National Museum. Its prized exhibit, the Lion Throne of King Thibaw (the last monarch of Burma) stood centre stage beneath a beautiful rotunda with a domed ceiling. Only in 1996 did the entire museum move into its dedicated premises on Pyay Road (now the National Museum). Today parts of the building are occupied by the Myanma Agricultural Development Bank, one of the country’s state-owned banks. Perhaps one day, this proud bank building will belong to one of the many offshoots that once owned Grindlays, the National Bank of India or the merged National and Grindlays. Among them are global players such as NatWest, Citibank, Lloyd’s and Standard Chartered. In 2000, the latter acquired the bank from none other than the Australia and New Zealand Banking Group (ANZ). It was the only Western bank to receive a coveted licence from Myanmar authorities in 2014.

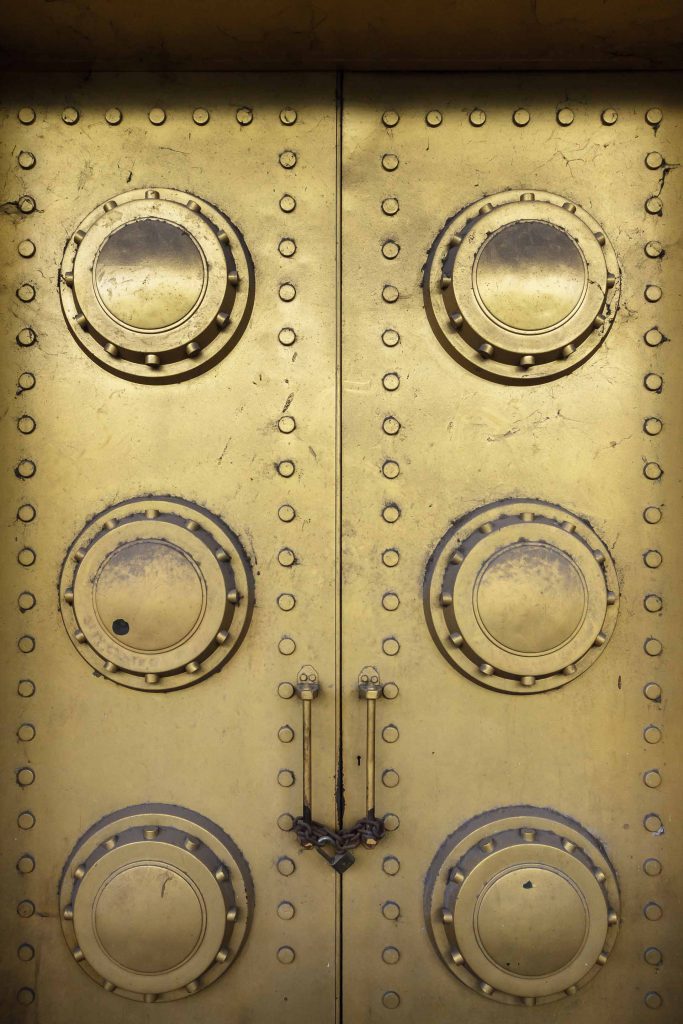

This imposing building, with its strictly geometric façade, is another reason why this stretch of Pansodan Street should be one of Yangon’s most treasured and protected thoroughfares. The columns don’t follow classical rules: they connect without any capitals. The underside of the protruding roofs is decorated with scales. Lion-headed waterspouts decorate the roofline. The small windows are set back from the columns. They are surrounded by an arched geometric pattern. The large semi-circular entrance canopy cantilevers over the sidewalk and extends onto the street, like most other roofs on this side of Pansodan Street. Remarkably, it also features a mirrored underside. The golden entrance door is worth admiring too. But at the time of writing, entry was not permitted.

My father ran the Bank of India in this building from approximately 1946 to 1954.