Yangon’s modern age began in 1852 with a master plan cooked up by British colonial officers. Their rectilinear street grid still defines the downtown area. With the country’s recent opening-up, Yangon’s population is expected to double in the coming decades. A comprehensive urban plan will cause frictions but is undoubtedly needed.

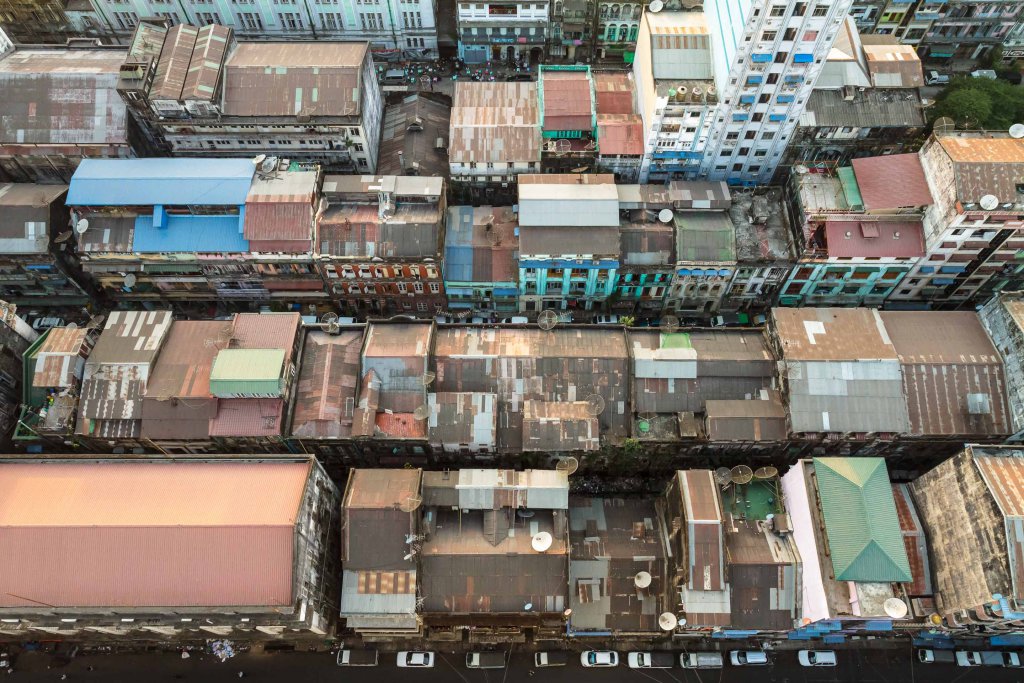

Yangon was shattered by the Second Anglo–Burmese War in 1852. The British then set about turning the small, swampy town into a capital for their latest colonial possession. William Montgomerie drew up a master plan, and Lieutenant A. Fraser later amended it. Both belonged to the Bengal Engineers, a corps of British colonial officers. Their plan proposed a wide Strand Road along the river and a grid of streets leading north. They placed the Sule Pagoda at the city’s heart. The city would cover an area measuring about 4.25 kilometres in length, east to west, and a kilometre in width. This is roughly today’s downtown—what local planners refer to as the “central business district” (CBD). The northern boundary was defined by the railway planned there in the 1870s, and the land beyond that line was the site of the Shwedagon Pagoda, partially surrounded by the British cantonment areas. Burmese villages dotted the landscape farther afield.

This downtown/uptown distinction remains a feature of today’s Yangon. The colonial city first grew within the confines of the downtown area, expanding east and west until it reached the waterways. Large swamps were drained and cleared. Public infrastructure was gradually installed, with sewage becoming a particular challenge in an increasingly overcrowded city. People went around by steam tram, electric tramway and motor buses, often operated by private companies. A large part of the economic activity was concentrated on the southern waterfront with docks, jetties, warehouses and wharfs dominating the shore.

“Myanmar’s economy is opening, but the bulk of foreign investment remains focused on Yangon”

The post-independence era saw much of the new government’s scarce resources go to post-war reconstruction efforts rather than a comprehensive overhaul of the urban layout. The city expanded from the downtown core as important public services such as universities, hospitals and cultural institutions were constructed in the northern townships. Because Yangon was Myanmar’s capital until the move to Naypyidaw in 2005, national ministries and the armed forces administration continued to operate here. The most intrusive interventions to Yangon’s urban fabric occurred when the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) took power after the 1988 protests. These included extensive slum clearance programmes, the narrowing of pavements and an overhaul of public transport (for more information, refer to the section on post-1988 changes).

Myanmar’s economy is opening, but the bulk of foreign investment remains focused on Yangon. The city’s population is set to grow from today’s six million to above 10 million in the next two decades. Yangon urgently needs a comprehensive planning framework, including a zoning plan—and the institutional capacity to see it implemented. This plan was about 60 per cent complete at the time of writing.

There are plenty of challenges. Density in the CBD is reaching its limits and new high-rise construction would put even greater pressure on today’s overcrowded roads. However, there is a huge need for quality office space and—more importantly—affordable housing. Meanwhile, the city’s precious urban heritage begs for protection, and an enviable waterfront is monopolised by industrial zones. (The local conservation and urban planning charity, the Yangon Heritage Trust, proposes to redevelop the waterfront to include public uses.)

Yangon’s municipal authority, the Yangon City Development Committee (YCDC), is in charge of urban planning. According to Dr Kyaw Lat, a consultant working for YCDC, we can expect the following: in the short term, traffic management systems and a bus rapid transport (BRT) system will provide immediate relief to congestion. High-rise construction in the CBD has already been frozen to avoid further densification. The more contentious intervention is planned for the medium term. A flyover above Strand Road will become the southern perimeter of an inner ring road highway. From the waterfront, this would totally obscure the view of Strand Road and its stunning line-up of heritage façades. The plans already exist, and the overall project is set to cost about 2 billion US dollars. In the long term, an outer ring road will span the city’s wider circumference, reaching all the way south beyond Dala and as far north as Hlawga National Park. A bridge connecting the two sides of the Yangon River will also lead to further development on the other side. In the long term, Dr Kyaw Lat foresees a skytrain system operating in Yangon—as it does in Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur and Singapore.

The Yangon Heritage Trust’s Director, Daw Moe Moe Lwin, is also the Vice President of the Association of Myanmar Architects. She says flyovers are not the only solution to the worsening traffic problems; there are other options. “Why are vehicle owners privileged?” she asks. “Other cities have shown that increasing the street surface area also increases car ownership. Moreover, construction activities will prove hugely disruptive.” While it is true that Yangon is choking on traffic, the resolution suggested by YCDC may only make things worse in the short to medium term. As a non-governmental lobbyist the YHT’s power is limited, although it works closely with YCDC in spite of these differences of opinion. Nonetheless, Daw Moe Moe Lwin laments the lack of public consultation, for example in the recent construction of a vast pedestrian overpass on Strand Road.

Many other urban planning questions will need to be answered over the coming years. Japan’s aid agency JICA is providing technical assistance in urban planning and has devised a master plan for Yangon’s future development stretching to 2040. It sets out a vision of a megalopolis with new sub-centres growing in today’s periphery, connected by a much denser grid of transportation infrastructure. While such long-term planning is important, it has two shortcomings in this case: despite rapid growth, Myanmar will remain a poor country for years to come, limiting its financial resources. This will reduce the scope for suggested solutions, such as road tunnels and underground metro lines, and mean more widespread use of cheaper, but eventually more intrusive methods, such as flyovers and skytrains. And while relative political change is accompanying the country’s economic opening-up, democratic participation still lags far behind.

Local elections for the YCDC were held in late December 2014—a first for Yangon. These were marred by low turnout and a controversial “one vote per household” system, reminiscent of the days before universal suffrage in other countries. But civil society and YCDC seem willing to begin a dialogue. We can only hope that in future, crucial matters of urban planning will be debated in public.

Further reading:

Japan International Cooperation Agency, JICA. Yangon Urban Transport Master Plan: Major Findings on Yangon Urban Transport and Short-Term Actions. 2014.

Spate, OHK and Trueblood, LW (1942). “Rangoon: A Study in Urban Geography.” Geographical Review, 32.1 (1942): 56-73.